At 6:31 p.m. EST on Friday, 27 January 1967, as night fell over Cape Kennedy in Florida, one of the worst disasters ever to befall America’s space program unfolded with horrifying suddenness. Out at the Cape’s Pad 34 sat a two-stage Saturn IB booster, capped with the Command and Service Module (CSM) for Apollo 1. In less than a month’s time, it was hoped, Apollo 1 Command Pilot Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Senior Pilot Ed White—who had already earned fame as the United States’ first spacewalker—and Pilot Roger Chaffee would fly the new spacecraft for the first time in a crewed capacity in low-Earth orbit. As outlined in a recent AmericaSpace history article, those plans turned figuratively and literally to ashes in a tragedy forever known as “The Fire.”

As America remembers the disaster which claimed Apollo 1, on this date, five decades ago, AmericaSpace honors the three men whose careers had already carried them to exalted heights … and, had the hands of fate been kinder, might have taken them further still.

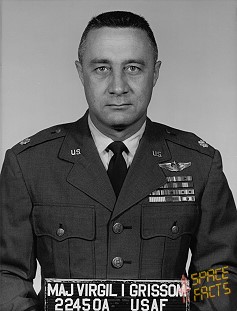

“I’m a pilot. Isn’t that enough?”

Virgil Ivan Grissom had already established himself as America’s second man in space, the first NASA astronaut to make two space missions and the first human to eat a corned-beef sandwich aboard an Earth-circling spacecraft by the time of Apollo 1. Born in the Midwestern town of Mitchell, Ind., on 3 April 1926, he was nicknamed “Greasy Grissom” as a child and his small stature—just five feet and four inches—led him to grow up with a determination to “prove I could do things as well as the big boys.”

His father worked for almost a half-century on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and Grissom, though too small to participate in many school sports, joined the Boy Scouts and led the Honor Guard. He delivered newspapers and, in the summer, picked peaches and cherries for local growers in order to earn enough money to date his sweetheart, Betty Moore. The couple married in July 1945. Grissom was described by his school principal as “an average, solid citizen, who studied just about enough to get a diploma,” but his lasting regret was being unable to fight for his country in the theater of World War II.

Nevertheless, he served a spell as an aviation cadet, then left the Air Force to work on installing doors on school buses. He entered Purdue University to study mechanical engineering, with Betty working as a long-distance operator and Grissom flipping burgers at a diner to make ends meet. He earned his degree in 1950—and, touchingly, credited his wife for having made it possible—and re-enlisted in the Air Force. After cadet training, Grissom won his wings and was deployed to Korea, where he flew 100 combat missions in F-86 Sabre jets, as part of the 334th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron.

Early each morning, the pilots rode an old school bus from the hangar to the flight line and only those who had been involved in air-to-air combat were permitted seats. The uninitiated had to stand. Grissom stood only once.

He returned to the United States and was stationed at Bryan Air Force Base in Texas, where he schooled trainee pilots, and undertook a degree in aeronautical engineering at the Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. In late 1956, Grissom was selected for test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., by which he time he had accrued more than 3,000 hours of flying time and a reputation as one of the best pilots in America. A couple of years later, early in 1959, he received top secret instructions to report to Washington, D.C., in civilian clothes, for a classified briefing.

That briefing was his first introduction to Project Mercury: the United States’ effort to place a man into space. During the intense physical and psychological screening which followed, he ran on the treadmill—his heart rate soaring at close to 200 beats per minute at one stage—and kept himself cool whilst seated in a heat chamber, by reading a dog-eared copy of Reader’s Digest. When the doctors discovered that Grissom was a hay fever sufferer, his response was priceless. Without missing a beat, he told them that he did not expect there to be an abundance of ragweed pollen in space and that he would be fine.

“I tried not to give the headshrinkers anything more than they were actually looking for,” he said of the psychological tests. “I played it cool and tried not to talk myself into a hole.” It worked and, in April 1959, Grissom was selected as one of America’s “Mercury Seven” astronauts. Less than two years later, he was assigned, along with Al Shepard and John Glenn, to train for the first piloted Mercury mission and in July 1961 wound up flying a suborbital “hop” atop the Mercury-Redstone 4 vehicle, in a bell-shaped capsule which he had dubbed “Liberty Bell 7.” As detailed previously in an AmericaSpace history article, the 15-minute flight was successful, but after splashdown Liberty Bell 7’s hatch blew prematurely. The spacecraft sank in the Atlantic Ocean and Grissom nearly drowned. Not for four decades would it be retrieved, leading to allegations over the years that Grissom was at fault—an allegation he denied to the day he died.

The incident did nothing to tarnish his career, however, and by April 1964 he was training with “rookie” spacefarer John Young to fly the first two-man Gemini mission. Among the astronauts, Gemini earned itself the nickname “Gusmobile,” because Grissom was the only astronaut small enough to scrunch himself down into his seat, with enough overhead clearance to close the hatch. He and Young launched aboard Gemini 3 on 23 March 1965 and their flight lasted just shy of five hours, running the new spacecraft through its paces.

In an unexpected highlight of the mission, Young had smuggled a corned-beef sandwich aboard and handed it to his command pilot. “I was concentrating on our spacecraft’s performance,” Grissom said later, “when suddenly John asked me: ‘You care for a corned-beef sandwich, skipper?’ If I could have fallen out of my couch, I would have! Sure enough, he was holding an honest-to-john corned-beef sandwich!” It had been sneaked aboard, courtesy of the Gemini 3 backup crew—Tom Stafford and the intrepid astronaut jokester Wally Schirra—and only a few bits of rye bread floating around the cabin eventually obliged Grissom to put it away.

Within weeks of returning to Earth, Grissom and Young were reassigned as the backup crew for Gemini VI, scheduled to perform the world’s first piloted space rendezvous, later in 1965. Following this assignment, in early 1966, Grissom was named as Command Pilot for the first manned Apollo mission, initially scheduled to launch atop a Saturn IB booster in the fall of that same year. In March, NASA formally announced Grissom’s assignment, together with veteran astronaut Ed White as Senior Pilot and “rookie” Roger Chaffee as Pilot.

The trio would train for a mission lasting anywhere up to 14 days in duration, during which they would evaluate the capabilities of the Block I Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM). Technical and other troubles eventually pushed Apollo 1 into the spring of 1967, with the third week of February shaping up as the likely launch date at the time of The Fire. Had the mission run as planned, Grissom would have become the first human to complete three spaceflights, as well as the first person to launch aboard three different types of spacecraft and atop three different boosters. Had he survived, there remains a strong possibility that Grissom might have been the first man on the Moon.

But for Grissom himself, the important element was flying. He disliked the “astronaut” moniker with intensity. “I’m not ass-anything,” he once retorted to a question. “I’m a pilot. Isn’t that enough?”

“Two full-course dinners, then dessert”

Long before his untimely death, aged 36, aboard Apollo 1, Edward Higgins White II had cemented his credentials as a record-setter in America’s space program. For on 3 June 1965, on his one and only space mission, the Air Force major became the first U.S. citizen to leave the confines of his spacecraft and perform a session of Extravehicular Activity (EVA). In so doing, White became the second human to perform a spacewalk—after Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov—and, at the time of writing, he stands as the third least-experienced spacewalker of all time. Yet the time spent in near-total vacuum by White on 3 June 1965 were pivotal in turning America’s fortunes around and taking the lead in the space race back from the Soviet Union.

Son of a West Point graduate and Air Force major-general, White was born in San Antonio, Texas, on 14 November 1930. Self-discipline, persistence, and a determination to achieve personal goals was a mantra for his early life. He first took the controls of an aircraft, under his father’s supervision, at the age of 12, and throughout his childhood the White family traveled to bases across the United States, from the East Coast to Hawaii. There was never any question that White would follow in his father’s footsteps to West Point. Whist at the Military Academy, he excelled in academics and athletics, serving as half-back on the football team, making the track team, and setting a new record in the 400-meter hurdles. So impressive were his credentials that he missed selection for the United States’ track team in the 1952 Olympics … by just 0.4 seconds.

Whilst at West Point, he met his future wife, Pat Finnegan, and upon graduation in 1952 enlisted in the Air Force. Initial flight instruction in Florida and receipt of his wings were followed by assignments in Germany, where he piloted F-86 Sabre and F-100 Super Sabre jets and completed the Air Force Survival School. Toward the end of the decade, as America readied for Project Mercury, White decided that he would aim for a NASA career and enrolled on a master’s degree program at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. He graduated in aeronautical engineering in 1959, having studied alongside another Air Force officer, named Jim McDivitt. Little did both men know that they would wind up in the same NASA astronaut class and would fly into space together.

With his master’s degree done, White attended test pilot school and subsequently evaluated research and weapons systems at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. During this period, he flew cargo aircraft on parabolas to prepare the Mercury astronauts-to-be for their missions. Two of his passengers were Deke Slayton and John Glenn, as well as the chimpanzees Enos and Ham. In flying these missions, White estimated that he “went weightless” at least 1,200 times before his selection by NASA.

In September 1962, White was selected as the youngest of the “New Nine” astronaut candidates, a few weeks ahead of his 32nd birthday. In addition to his intelligence, he gained a reputation as one of the most physically fit members of NASA’s corps: playing volleyball, handball, squash, and golf, jogging long-distance on the daily basis, biking to work, and even squeezing a rubber ball whilst running to build strength in his hands and arms. White set up a climbing rope in his backyard and could perform 50 sit-ups and 50 press-ups, back to back, without so much as a sharp intake of breath. It was said that he could “put away two full-course dinners at one sitting, then ask for dessert with a straight face!”

One night in early 1964, a fire broke out in the neighboring home of fellow astronaut Neil Armstrong and his wife, Janet. Their backyards were separated by a tall fence and White was first on the scene with a fire hose. “Still to this day,” wrote Armstrong’s biographer James Hansen in First Man, “Janet vividly recalls the image of Ed White clearing her six-foot fence. He took one leap and he was over.”

In July 1964, White and McDivitt were named as the prime crew for Gemini IV, which was initially planned as a seven-day test flight of the new spacecraft’s long-duration fuel cells; however, this objective was later moved to Gemini V. Right from the start, though, the public and press drew a link between Gemini IV and a possible spacewalk. At the press conference to announce the crew, it was stated that one of the astronauts might poke his helmeted head out of the spacecraft for a “stand-up” EVA. The plan was eventually approved in May 1965, just days before Gemini IV launched into orbit.

From 3-7 June, McDivitt and White embarked on the longest spaceflight ever attempted by U.S. astronauts at that time, logging 97 hours in orbit. In doing so, they fell short of securing the empirical world record—set by Soviet cosmonaut Valeri Bykovsky—for the longest piloted space mission by less than 22 hours. Yet White’s EVA, during which he maneuvered himself around the exterior of Gemini IV, using a hand-held pressurized gas “gun,” lasted more than double that of Leonov’s spacewalk. By the time he returned inside the spacewalk, White had been in vacuum for 36 minutes.

Returning from his first mission, White was assigned as backup command pilot for Gemini VII, which took place in December 1965. According to the informal three-flight crew-rotation system, this might have positioned himself and Mike Collins as prime crew for Gemini X in the summer of 1966. However, White’s career was heading toward Project Apollo—the effort to land a man on the Moon, before the decade’s end—and in March 1966 he was formally assigned, with Grissom and Chaffee, to Apollo 1. Had the mission flown to its maximum duration of 14 days, it would have positioned White in first or second place on the list of most flight-seasoned spacefarers at that time—approaching, or even exceeding, the 18-day career total established in November 1966 by fellow astronaut Jim Lovell.

“One of the smartest boys I’ve ever run into”

The third member of the ill-fated Apollo 1 crew, and the flight’s only “rookie,” might have become the youngest American in history to complete a space mission. In fact, had Roger Bruce Chaffee launched atop the Saturn IB booster on 21 February 1967, just six days after his 32nd birthday, he would have eclipsed his best friend Gene Cernan and, indeed, would have established a record which would have endured to this day. Even in more recent times, astronauts Sally Ride, Steve Hawley, and Tammy Jernigan—all of whom made their first flights aged 32—would not have been quite “young enough” to have beaten the record so cruelly snatched from Chaffee.

That said, his youth belied a talented aviator and a skilled engineer. Chaffee came from Grand Rapids, Mich., where he was born on 15 February 1935, the son of a barnstorming biplane pilot. Aged seven, he was taken flying by his father over Lake Michigan and a fascination with aviation was nurtured. As father and son built model aircraft, the young Chaffee also developed an interest in guns and hunting from his grandfather and a love of music led him to play the French horn, the cornet, and the trumpet.

Within a year of joining the Boy Scouts in 1948, he earned ten badges and the Order of the Arrow, before eventually rising to Eagle Scout and teaching swimming. An interest in mathematics and chemistry led him first to Illinois State University in September 1953 for a year, during which time he settled on aeronautical engineering as a major, then transferred to Purdue. As a Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) scholar, he undertook summer duty aboard the battleship Wisconsin. His undergraduate career also saw him teaching freshman mathematics classes and in September 1955 he met Martha Horn, who became his wife, two years later.

A naval career beckoned, as did flight training. Chaffee soloed in March 1957 and earned his degree in aeronautical engineering, before being commissioned as an Ensign. After military flight instruction, he flew the T-34 Mentor and T-28 Trojan aircraft, then began training on the F-9F Cougar jet. Subsequent assignments included the A-3D Skywarrior photographic reconnaissance aircraft, as well as safety and reliability control issues, and overflew Cuba during the dark days of the missile crisis in October 1962.

By the middle of the following year, he was working towards a master’s degree in reliability engineering at the Air Force Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, but in June was summoned to Houston, Texas, for screening as part of NASA’s next class of astronauts. That October, Chaffee—like Ed White before him—became the youngest member of his class, when he was selected alongside 13 other pilots to become the space agency’s third group of astronaut hopefuls.

“In the early days, some tended to underestimate Roger, perhaps because of his small stature,” reflected fellow astronaut Walt Cunningham in his memoir, The All-American Boys, “but he had the capacity to fill a room—any room. It was impossible to attend a meeting with Roger and not be aware of his presence. He had a fighter pilot’s attitude, even though his flying background was in multi-engine photo-reconnaissance aircraft. When confronted with a problem, Roger would bore right in.”

His energy and enthusiasm were legendary. At one time, Martha asked her husband to build a tiny water fountain the backyard, to which Chaffee constructed a waterfall from tons of gravel and hours of backbreaking work. The Chaffees had the first swimming pool on their block, remembered neighbor Gene Cernan, who had built a walk-in bar in his family room, and the pair hosted many parties. A self-confessed workaholic, Chaffee periodically went hunting with Cernan and hand-crafted his own weapons.

Early in 1966, Chaffee’s hard work at NASA was rewarded with assignment to the third seat on the very first piloted Apollo mission. Despite his age, he very quickly gained the respect of his crewmates. “Roger is one of the smartest boys I’ve ever run into,” said Gus Grissom in one of his final interviews to The New York Times. “He’s just a damn good engineer. There’s no other way to explain it. When he starts talking to engineers about their systems, he can just tear those damn guys apart.”

Had Chaffee flown in February 1967, he would have established a new record as the youngest American ever launched into space, aged 32 years and six days. This would have surpassed Cernan’s record of 32 years and 81 days at the time of his Gemini IX-A mission. In fact, even the current record-holder, Tammy Jernigan, was 32 years and 29 days old when she launched aboard Shuttle Columbia on STS-40 in June 1991. Therefore, had Chaffee flown on time, he would have secured a record—and held it—for at least a half-century.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » Apollo » Missions » Apollo » Apollo 1 »